Predictors Of Difficult Intubation: Study In Kashmiri Population

Arun Kr. Gupta , Mohamad Ommid , Showkat Nengroo , Imtiyaz Naqash and Anjali Mehta

Cite this article as: BJMP 2010;3(1):307

|

| ABSTRACT Airway assessment is the most important aspect of anaesthetic practice as a difficult intubation may be unanticipated. A prospective study was done to compare the efficacy of airway parameters to predict difficult intubation. Parameters studied were degree of head extension, thyromental distance, inter incisor gap, grading of prognathism, obesity and modified mallampati classification. 600 Patients with ASA I& ASA II grade were enrolled in the study. All patients were preoperatively assessed for airway parameters. Intra-operatively all patients were classified according to Cormack and Lehane laryngoscopic view. Clinical data of each test was collected, tabulated and analyzed to obtain the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value & negative predictive value. Results obtained showed an incidence of difficult intubation of 3.3 % of patients. Head and neck movements had the highest sensitivity (86.36%); high arched palate had the highest specificity (99.38%). Head and neck movements strongly correlated for patients with difficult intubation. KEYWORDS Intubation, Anaesthesia, Laryngoscopy |

The fundamental responsibility of an anesthesiologist is to

maintain adequate gas exchange through a patent airway. Failure to

maintain a patent airway for more than a few minutes results in brain

damage or death1. Anaesthesia in a patient with a difficult

airway can lead to both direct airway trauma and morbidity from hypoxia

and hypercarbia. Direct airway trauma occurs because the management of

the difficult airway often involves the application of more physical

force to the patient’s airway than is normally used. Much of the

morbidity specifically attributable to managing a difficult airway comes

from an interruption of gas exchange (hypoxia and hypercapnia), which

may then cause brain damage and cardiovascular activation or depression2.

Though endotracheal intubation is a routine procedure for all

anesthesiologists, occasions may arise when even an experienced

anesthesiologist might have great difficulty in the technique of

intubation for successful control of the airway. As difficult intubation

occurs infrequently and is not easy to define, research has been

directed at predicting difficult laryngoscopy, i.e. when is not possible

to visualize any portion of the vocal cords after multiple attempts at

conventional laryngoscopy. It is argued that if difficult laryngoscopy

has been predicted and intubation is essential, skilled assistance and

specialist equipment should be provided. Although the incidence of

difficult or failed tracheal intubation is comparatively low, unexpected

difficulties and poorly managed situations may result in a life

threatening condition or even death3.

Difficulty in intubation is usually associated with difficulty in

exposing the glottis by direct laryngoscopy. This involves a series of

manoeuvres, including extending the head, opening the mouth, displacing

and compressing the tongue into the submandibular space and lifting the

mandible forward. The ease or difficulty in performing each of these

manoeuvres can be assessed by one or more parameters4.

Extension of the head at the atlanto-occipital joint can be

assessed by simply looking at the movements of the head, measuring the

sternomental distance, or by using devices to measure the angle5.

Mouth opening can be assessed by measuring the distance between upper

and lower incisors with the mouth fully open. The ease of lifting the

mandible can be assessed by comparing the relative position of the lower

incisors in comparison with the upper incisors after forward protrusion

of the mandible6. The measurement of the mento-hyoid distance and thyromental distance provide a rough estimate of the submandibular space7.

The ability of the patient to move the lower incisor in front of the

upper incisor tells us about jaw movement. The classification provided

by Mallampati et al8 and later modified by Samsoon and Young9

helps to assess the size of tongue relative to the oropharynx.

Abnormalities in one or more of these parameters may help predict

difficulty in direct laryngoscopy1.

Initial studies attempted to compare individual parameters to predict difficult intubation with mixed results8,9. Later studies have attempted to create a scoring system3,10 or a complex mathematical model11,12.

This study is an attempt to verify which of these factors are

significantly associated with difficult exposure of glottis and to rank

them according to the strength of association.

read more..........

read more..........

Materials & methods

The study was conducted after obtaining institutional review board

approval. Six hundred ASA I & II adult patients, scheduled for

various elective procedures under general anesthesia, were included in

the study after obtaining informed consent. Patients with gross

abnormalities of the airway were excluded from the study. All patients

were assessed the evening before surgery by a single observer. The

details of airway assessment are given in Table I.

Table I: Method of assessment of various airway parameters (predictors)

Airway Parameter

|

Method of assessment

|

Modified Mallampati Scoring

|

Class I: Faucial pillars, soft palate and uvula visible.

Class II: Soft palate and base of uvula seen

Class III: Only soft palate visible.

Class IV: Soft palate not seen

Class I & II : Easy Intubation

Class III & IV: Difficult Intubation

|

Obesity

|

Obese BMI (≥ 25)

Non Obese BMI (< 25)

|

Inter Incisor Gap

|

Distance between the incisors with mouth fully open(cms)

|

Thyromental distance

|

Distance between the tip of thyroid cartilage and tip of chin, with fully extended(cms)

|

Degree of Head Extension

|

Grade I ≥ 90◦

Grade II = 80◦-90◦

Grade III < 80◦

|

Grading of Prognathism

|

Class A: - Lower incisor protruded anterior to the upper incisor.

Class B: - Lower incisor brought edge to edge with upper incisor but not anterior to them.

Class C: - Lower incisors could be brought edge to edge.

|

In addition the patients were examined for the following.

- High arched palate.

- Protruding maximally incisor (Buck teeth)

- Wide & short Neck

Direct laryngoscopy with Macintosh blade was performed by an anaesthetist who was blinded to preoperative assessment.

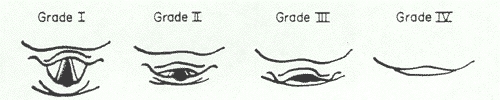

Glottic exposure was graded as per Cormack-Lehane classification13 (Fig 1).

Figure 1: Cormack-Lehane grading of glottic exposure on direct laryngoscopy

Grade 1: most of the glottis visible; Grade 2: only the

posterior extremity of the glottis and the epiglottis visible; Grade 3:

no part of the glottis visible, only the epiglottis seen; Grade 4: not

even the epiglottis seen. Grades 1 and 2 were considered as ‘easy’ and

grades 3 and 4 as ‘difficult’.

Results

Glottic exposure on direct laryngoscopy was difficult in 20 (3.3%) patients.

The frequency of patients in various categories of ‘predictor’ variables is given in Table-II

Table II: The frequency analysis of predictor parameters

Airway Parameter

|

Group

|

Frequency (%)

|

Modified Mallampati Scoring

|

Class 1&2

Class 3&4

|

96%

4%

|

Obesity

|

Obese BMI (≥ 25)

Non Obese BMI (< 25)

|

28.7%

71.3%

|

Inter Incisor Gap

|

Class I : >4cm

Class II: <4cm

|

93.5%

6.5%

|

Thyromental distance

|

Class I: ≥ 6cm.

Class II: ≤6cm.

|

94.6%

5.4%

|

Head & Neck Movements

|

Difficult {class II & III (90˚)}

Easy {class I(>90˚)}

|

16%

84%

|

Grading of Prognathism

|

Difficult (class III)

Easy (class I + II)

|

96.1%

3.9%

|

Wide and Short neck

|

Normal neck body ratio 1:13

Difficult (Ratio≥ 1:13)

|

86.9%

13.1%

|

High arched Palate

|

Yes

No

|

1.9%

98.1%

|

Protruding Incisors

|

Yes

No

|

4.2%

95.8%

|

The association between different variables and difficulty in

intubation was evaluated using the chi-square test for qualitative data

and the student’s test for quantitative data and p<0.05 was regarded

as significant. The clinical data of each test was used to obtain the

sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive

values. Results are shown in Table III.

Table III: Comparative analysis of various physical factors and scoring systems

Physical factors and various Scoring Systems

|

Sensitivity ( % )

|

Specificity ( % )

|

PPV

( % )

|

NPV

( % )

|

Obesity

|

81.8

|

72.76

|

6.34

|

99.43

|

Inter incisor gap

|

18.8

|

94.14

|

6.6

|

98.1

|

Thyromental distance

|

72.7

|

96.5

|

32.0

|

99.4

|

Head and Neck movement

|

86.36

|

86.0

|

34.6

|

99.7

|

Prognathism

|

4.5

|

96.3

|

2.7

|

97.9

|

Wide and Short neck

|

45.5

|

87.9

|

7.8

|

98.6

|

High arched palate

|

40.1

|

99.38

|

60.0

|

98.67

|

Protruding incisor

|

4.6

|

95.9

|

2.5

|

97.79

|

Mallampati scoring system

|

77.3

|

98.2

|

48.57

|

99.5

|

Cormack and Lehane’s scoring system

|

100

|

99.7

|

88

|

100

|

Discussion

Difficulty in endotracheal intubation constitutes an important

cause of morbidity and mortality, especially when it is not anticipated

preoperatively. This unexpected difficulty in intubation is the result

of a lack of accurate predictive tests and inadequate preoperative

assessment of the airway. Risk factors if identified at the preoperative

visit help to alert the anaesthetist so that alternative methods of

securing the airway can be used or additional expertise sought before

hand.

Direct laryngoscopy is the gold standard for tracheal intubation.

There is no single definition of difficult intubation but the ASA

defines it as occurring when “tracheal intubation requires multiple

attempts, in the presence or absence of tracheal pathology”. Difficult

glottic view on direct laryngoscopy is the most common cause of

difficult intubation. The incidence of difficult intubation in this

study is similar to that found in others.

As for as the predictors are concerned, different parameters for

the prediction of difficult airways have been studied. Restriction of

head and neck movement and decreased mandibular space have been

identified as important predictors in other studies. Mallampati

classification has been reported to be a good predictor by many but

found to be of limited value by others14. Interincisor

gap, forward movement of jaw and thyromental distance have produced

variable results in predicting difficult airways in previous studies7,15. Even though thyromental distance is a measure of mandibular space, it is influenced by degree of head extension.

There have been attempts to create various scores in the past. Many

of them could not be reproduced by others or were shown to be of

limited practical value. Complicated mathematical models based on

clinical and/or radiological parameters have been proposed in the past16,

but these are difficult to understand and follow in clinical settings.

Many of these studies consider all the parameters to be of equal

importance.

Instead of trying to find ‘ideal’ predictor(s), scores or models,

we simply arranged them in an order based on the strength of association

with difficult intubation. Restricted extension of head, decreased

thyromental distance and poor Mallampati class are significantly

associated with difficult intubation.

In other words patients with decreased head extension are at much

higher risk of having a difficult intubation compared to those with

abnormalities in other parameters. The type of equipment needed can be

chosen according to the parameter which is abnormal. For example in a

patient with decreased mandibular space, it may be prudent to choose

devices which do not involve displacement of the tongue like the Bullard

laryngoscope or Fiber-optic laryngoscope. Similarly in patients with

decreased head extension devices like the McCoy Larngoscope are likely

to be more successful.

Conclusion

This prospective study assessed the efficacy of various parameters of airway assessment as predictors of difficult intubation. We have find that head and neck movements, high arched palate, thyromental distance & Modified Malampatti classification are the best predictors of difficult intubation.

This prospective study assessed the efficacy of various parameters of airway assessment as predictors of difficult intubation. We have find that head and neck movements, high arched palate, thyromental distance & Modified Malampatti classification are the best predictors of difficult intubation.

| Competing Interests None Declared Author Details ARUN KUMAR GUPTA, Dept. Of Anaesthesiology, Rural Medical College, Loni, MOHAMED OMMID, Dept. Of Anaesthesiology, SKIMS, Soura, J&K, India SHOWKAT NENGROO, Dept. Of Anaesthesiology, SKIMS, Soura, J&K,India IMTIYAZ NAQASH, Dept. Of Anaesthesiology, SKIMS, Soura, J&K,India ANJALI MEHTA, Dept. Of Anaesthesiology, GMC Jammu, J&K, India CORRESSPONDENCE: ARUN KUMAR GUPTA, Assistant Professor Dept. of Anaesthesiology & Critical Care Rural Medical College, Loni Maharashtra, India, 413736 Email: guptaarun71@yahoo.com |

References

1. Rose DK, Cohen MM. The airway: problems and predictions in 18,500 patients. Can J Anaesth 1994; 41:372-83.

2. Benumof JL: Management of the

difficult airway: With special emphasis on awake tracheal intubation.

Anesthesiology 1991; 75: 1087-1110

3. Wilson ME, Spiegelhalter D, Robertson JA, Lesser P. Predicting difficult intubation. Br J Anaesth 1988; 61(2):211-6.

4. A.Vasudevan, A.S.Badhe. Predictors of difficult intubation – a simple approach. The Internet Journal of Anesthesiology 2009; 20(2)

5. Tse JC, Rimm EB, Hussain A. Predicting

difficult endotracheal intubation in surgical patients scheduled for

general anesthesia: a prospective blind study. Anesth Analg 1995; 81(2):254-8.

6. Savva D. Prediction of difficult tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth 1994; 73(2):149-53.

7. Butler PJ, Dhara SS. Prediction of

difficult laryngoscopy: an assessment of the thyromental distance and

Mallampati predictive tests. Anaesth Intensive Care 1992; 20(2):139-42.

8. Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD,

Desai SP, Waraksa B, Freiberger D, et al. A clinical sign to predict

difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J 1985; 32(4):429-34.

9. Samsoon GL, Young JR. Difficult tracheal intubation: a retrospective study. Anaesthesia 1987; 42(5):487-90.

10. Nath G, Sekar M. Predicting difficult intubation--a comprehensive scoring system. Anaesth Intensive Care 1997; 25(5):482-6.

11. Charters P. Analysis of mathematical model for osseous factors in difficult intubation. Can J Anaesth 1994; 41(7):594-602.

12. Arne J, Descoins P, Fusciardi J, Ingrand P,

Ferrier B, Boudigues D, et al. Preoperative assessment for difficult

intubation in general and ENT surgery: predictive value of a clinical

multivariate risk index. Br J Anaesth 1998; 80(2):140-6.

13. Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia 1984; 39(11):1105-11.

14. Lee A, Fan LT, Gin T, Karmakar MK, Ngan Kee WD. A

systematic review (meta-analysis) of the accuracy of the Mallampati

tests to predict the difficult airway. Anesth Analg 2006; 102(6):1867-78.

15. Bilgin H, Ozyurt G. Screening tests for predicting difficult intubation. A clinical assessment in Turkish patients. Anaesth Intensive Care 1998; 26(4):382-6.

16. Naguib M, Malabarey T, AlSatli RA, Al Damegh S,

Samarkandi AH. Predictive models for difficult laryngoscopy and

intubation. A clinical, radiologic and three-dimensional computer

imaging study. Can J Anaesth 1999; 46(8):748-59.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar